By The TessDrive team

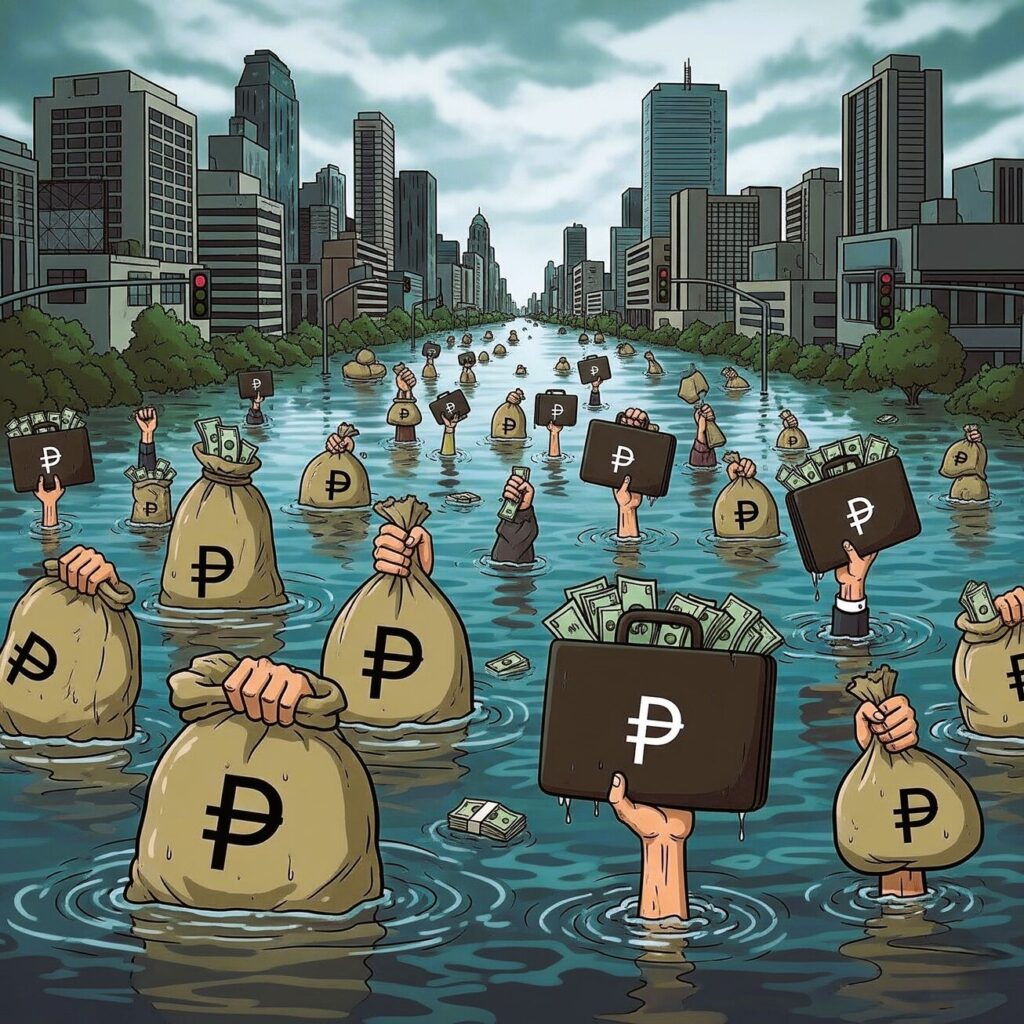

Callous, heartless, greedy.

That’s the consensus among Philippine netizens after the series of exposes on numerous contractors and politicians and their alleged unholy alliances, excessively profiting from billions of pesos of flood control project funds.

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, during his State of the Nation Address (SONA) last July 28, called for an audit of flood control projects and for accountability over alleged misuse of public funds. Former Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) Secretary Manuel Bonoan admitted that his agency had no system of monitoring a number of flood control and mitigation projects that congressmen inserted into the national budget at the last minute. Recently, several reports involving contractors of flood control projects linked to politicians and public officials have emerged.

The investigations—ordered by Marcos Jr—stemmed from the widespread and severe flooding that paralyzed the National Capital Region (NCR) just this July. Marcos disclosed on Aug. 11 that an initial review found that P100 billion worth, or nearly 20%, of all flood control projects in the past three years were undertaken by only 15 contractors, according to the report of the Presidential Communications Office (pco.gov.ph).

Citing the preliminary report of the DPWH, President Marcos said P545 billion in public funds went to flood control projects nationwide since July 2022. The department identified 2,409 contractors for both local and national flood control projects.

But there is a disturbing statistic buried in these figures, Marcos said. “Twenty percent of the entire P545-billion budget napunta lang sa 15 na contractors. Sa 15 na contractor na ‘yan, lima sa kanila ay may kontrata sa buong Pilipinas (20% of the entire P545-billion budget went only to 15 contractors. Of those 15 contractors, 5 of them had contracts around the entire country),” he said, as quoted by the PCO report.

With that, the President has thus ordered an audit to investigate the matter further.

Meanwhile, while we’re all getting drowned in numbers, the next big storms and typhoons of the season are building up and will inevitably hit the country, again and again. Each monsoon and typhoon season is not just a natural disaster, it highlights the systemic failure of our society and leadership to effectively address our response to extreme environmental phenomena, despite the certainty of these weather cycles to occur again, as sure as the sun rises in the East.

The perennial flooding in Metro Manila happens not because of the lack of plans or financing. Billions of pesos have been allocated and numerous master plans have been drafted over the decades. The very root cause lies in the political and institutional failures that have derailed these plans, rerouted the funds. Even the best laid-out plans with available budgets are guaranteed to fail due to a combination of disjointed leadership, a focus on short-term fixes instead of addressing root causes, and a persistent lack of accountability.

This report that the TessDrive team has put together discusses man-made disasters and puts the spotlight on Metro Manila’s chronic inundation, which is the predictable outcome of a dangerous convergence of factors: An inherent geographic and climatological vulnerability that has been catastrophically amplified by decades of governance failures, unsustainable urban development, and profound environmental degradation. These deeply entrenched, man-made vulnerabilities are now being pushed past their breaking point by the intensifying pressures of a rapidly changing global climate.

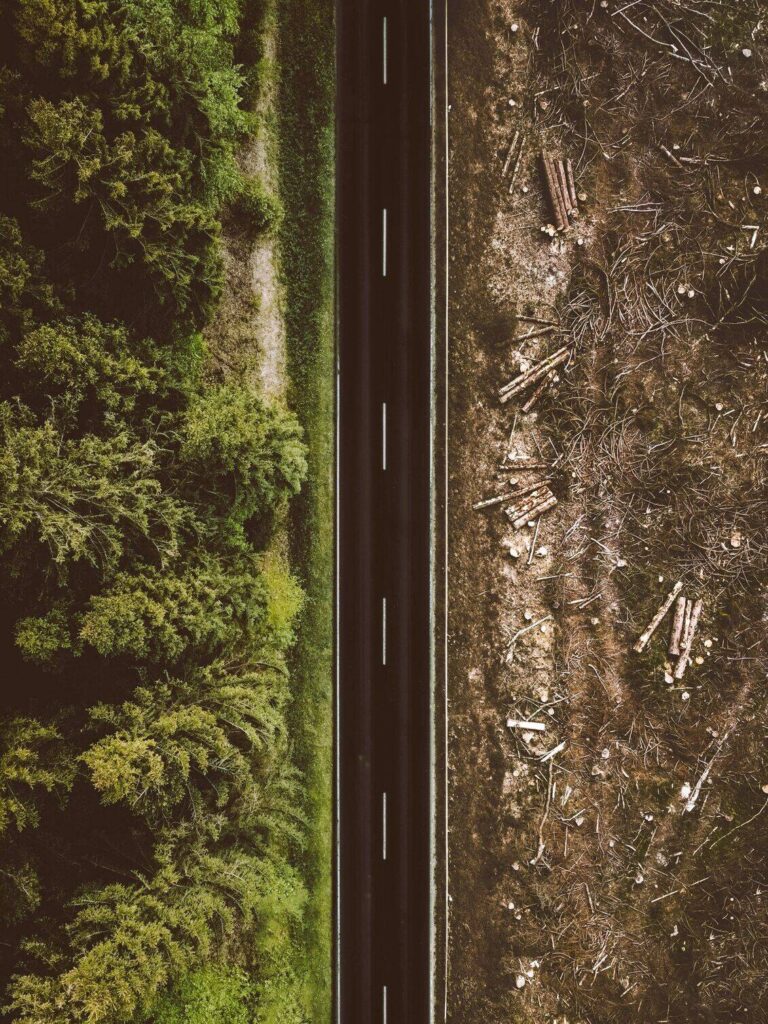

Floods due to loss of forest cover

The following ought to be raised for context first: The Philippines was mentioned several times internationally for its environment issues such as typhoons, flooding, deforestation, plastic pollution, landfill sites, waste dumps, indigenous people being harassed, displaced and killed for protecting their land, and how the country has become one of the most dangerous places on the planet to be an environmental defender.

Earth Policy Institute’s Lester R. Brown, author of the book “World On The Edge: How to prevent environmental and economic collapse,” wrote about flooding in the Philippines, among other countries. He said that there is much more to the story than the torrential rains as the cause.

Brown also talked about how protecting the 10 billion acres of remaining forests on Earth and replanting many of those that already lost their forest cover, for example, are both essential for restoring the earth’s health. He also pointed out that global deforestation has been concentrated in the developing world. He emphasized that planting trees on degraded or disturbed land not only reduces soil erosion but also helps pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

“Although banning deforestation may seem far-fetched, environmental damage has pushed Thailand, the Philippines, and China to implement partial or complete bans on logging. All three bans followed devastating floods and mudslides resulting from the loss of forest cover,” wrote Brown.

Filipino activist Mitzi Jonelle Tan in “The Climate Book” described how the Philippines has been one of the most climate-vulnerable places in the world. She also said that the country is also one of the most dangerous places on the planet to be an environmental defender.

“It isn’t fair that we have to grow up full of fear. Fear of the next bang of thunder from the storms that will wash away our homes. Fear of the next bang on our door from the police who will whisk us away from our loved ones.”

“As typhoons destroy our homes and floods rise, the people are rising up to break down systemic oppression. There’s a growing movement in my country, led by small farmers, fisherfolk, indigenous peoples and workers fighting for liberation. Together, we fight for land for the tillers, for reparations for the injustices perpetrated under imperialism, for a just transition into a greener society and for a world with a united community full of love and cooperation,” wrote Tan.

Vital waterways systematically choked

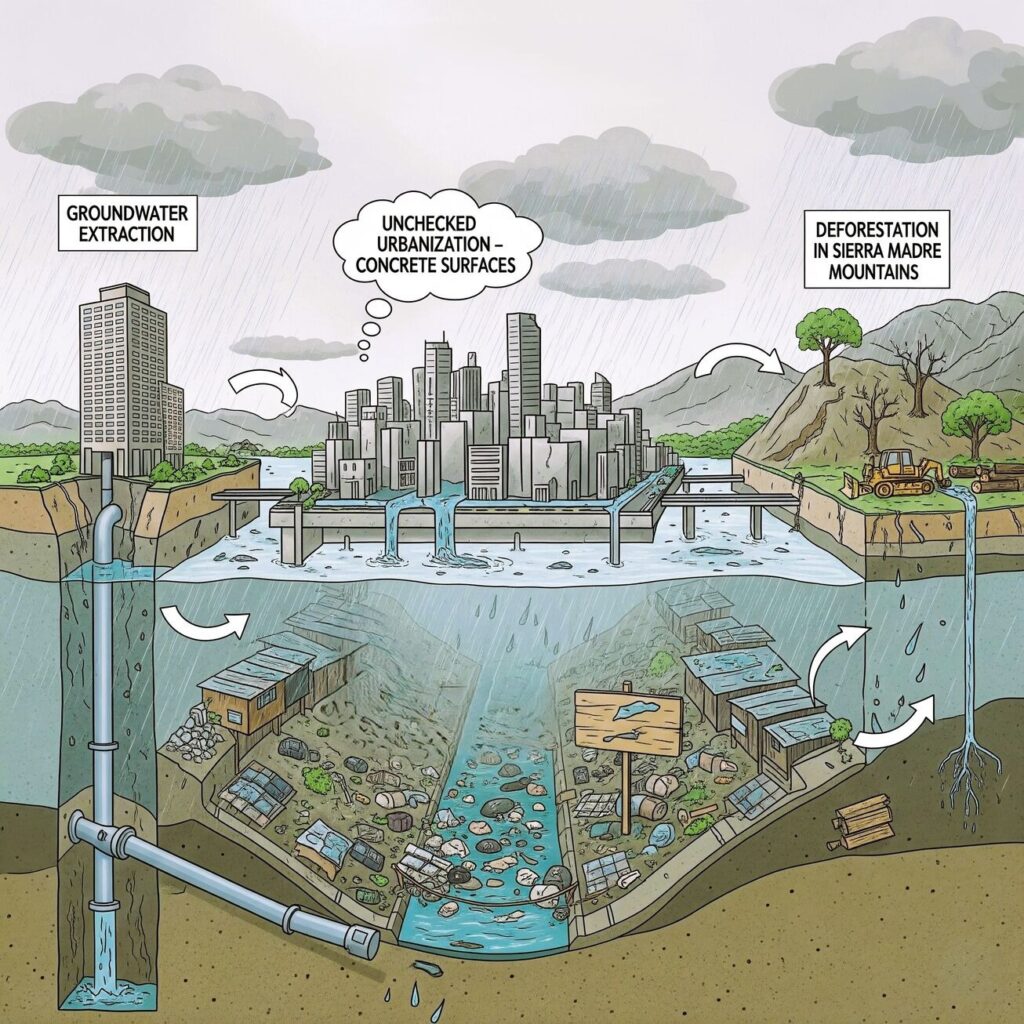

As Filipinos feel the nation’s capital literally sinking, many questions arise, demanding immediate answers. TessDrive has compiled multi-disciplinary analyses of a crisis with interlocking causes.

According to Greg Bankoff in his article “Flooding in Metro Manila: a historical perspective” in the International Institute for Asian Studies Newsletter (2003), one of those causes is unregulated groundwater extraction, causing the city to sink at an alarming rate, which in turn makes it more susceptible to floods. A relentless wave of unchecked urbanization has paved over natural drainage surfaces, replacing them with impervious concrete that transforms rainfall into overwhelming runoff. The city’s vital waterways—its natural and engineered arteries—are systematically choked by a solid waste management crisis of staggering proportions and constricted by the encroachment of informal settlements and other structures. Looking upstream, the critical watersheds of the Sierra Madre mountains, which once served as the region’s natural shield, have been dangerously eroded by deforestation, unleashing faster and larger volumes of water into the downstream metropolis.

Culpability for this crisis is systemic and shared. It lies within national government agencies that have failed to enforce laws, local government units that have presided over dysfunctional zoning and inadequate services, private sector actors who have prioritized profit over sustainability, and a governance structure that is too fragmented and politicized to implement effective, long-term solutions.

Joop Stoutjesdijk, who wrote the article “Philippines: Managing floods for inclusive and resilient development in Metro Manila” in preventionweb.net, mentioned that in 2012, the government launched a Flood Management Master Plan for Metro Manila, a comprehensive strategy funded by the World Bank. But sadly, this has languished for over a decade, crippled by a catastrophic implementation gap born of domestic bureaucratic inertia, funding shortfalls, and a lack of sustained political will.

The human cost of this failure is immense, disproportionately borne by the urban poor who are trapped in high-risk areas by economic necessity. Flooding is not just an inconvenience; it is a major driver of poverty, a destroyer of livelihoods, and a significant drag on the national economy.

Yet, this report concludes that a solution is not beyond reach. The technical knowledge, engineering strategies, and financial resources to build a resilient metropolis are largely available. However, achieving this requires a radical paradigm shift: Away from the failed, fragmented model of “flood control” and toward a holistic, integrated framework of “flood risk management”. This pathway is conditional upon fundamental institutional reform, the establishment of clear accountability, the rigorous enforcement of existing laws, and the mainstreaming of nature-based solutions alongside modernized infrastructure. Metro Manila is at a critical juncture. It can continue down the path of broken promises and predictable disaster, or it can summon the collective will to make the difficult but necessary choices to secure a resilient and sustainable future.

(To be continued)

End of Part 1